Piezoelectric transducer appendices (preliminary - v.6a, 2016-05-05)

Contents

- Appendix A: Comparison of 33 and 31 ceramic operation

- Appendix B: Manufacturer's piezoelectric cross-reference

- Appendix C: Method for applying prestress

- Appendix D: Ceramic dimensional specifications

- Appendix E: Ceramic electromechanical specifications

- Appendix F: Mechanical fits

- Appendix G: Understanding piezoelectric constants

- Appendix H: Effect of stack bolt on electromechanical coupling coefficient

- Appendix I: Resonance packet (pair)

- Appendix J: Comparison — series resonance and parallel resonance

Appendix A: Comparison of 33 and 31 ceramic operation

The ceramics that are used in power transducers fall into two categories.

- 33 type. For the 33 type the direction of ceramic vibration is parallel to the electric field. The ceramics are usually thin disks and the transducer uses multiple disks (generally at least one pair but sometimes as many as three or four pair, depending on the power handling requirements). This is the most common type.

- 31 type. For the 31 type the direction of ceramic vibration is perpendicular to the electric field. A single tube-shaped ceramic is typically used. This type is generally used only in special circumstances.

33 mode — Advantages

In a matched PZT4 parallel mode transducer, the strain and stress are less at a given driving electric field, but the bandwidth is up by a factor of 2.6 and the power by a factor of 1.7 compared to a matched PZT4 later mode transducer. (Morgan Technical Publication TP-221, pp. 14 - 15)

"The data in Tables XII and XIII show several advantages of the use of the parallel rather than the transverse mode in high power transducers. These include higher bandwidth, higher efficiency (\( e'_{em} \)) for the same power, and higher power for a given value of \( p_{DE} \) [electrical power dissipation]. Allowable bias stress is also higher in this mode." (Berlincourt (3), pp. 253, 255-256) Note particularly the PZT-4 data.

|

|

31 mode

The following are the advantages and disadvantages of using piezoelectric ceramics in the 31 mode. These may not all apply to a particular design or application.

Advantages

- Since the design may involve fewer parts (a single ceramic and one or two electrodes), the manufacturing costs may be less.

- Generally, a 31 design will have fewer ceramic interfaces so the mechanical loss from such interfaces is lower.

Disadvantages

- ".. approximately 5 times the ceramic is required to maintain the same output power level" compared to the 33 type. Channel Industries (1), p. 6

- The cost for electroding (inner and outer walls) is higher than for disks (33 type).

- The manufacturing cost may be higher because the yields for long cylinders may be lower than for disks (33 type).

- For a ceramic stack whose overall dimensions are identical, the frequency separation between series resonance (\( f_s \)) and parallel resonance (\( f_p \)) may be lower. Example: tube ceramic (0.650" OD x 0.300" ID x 1.000" long).

- The transducer may be difficult to mount at the node if ceramic tube spans the node.

zzz Insert table here

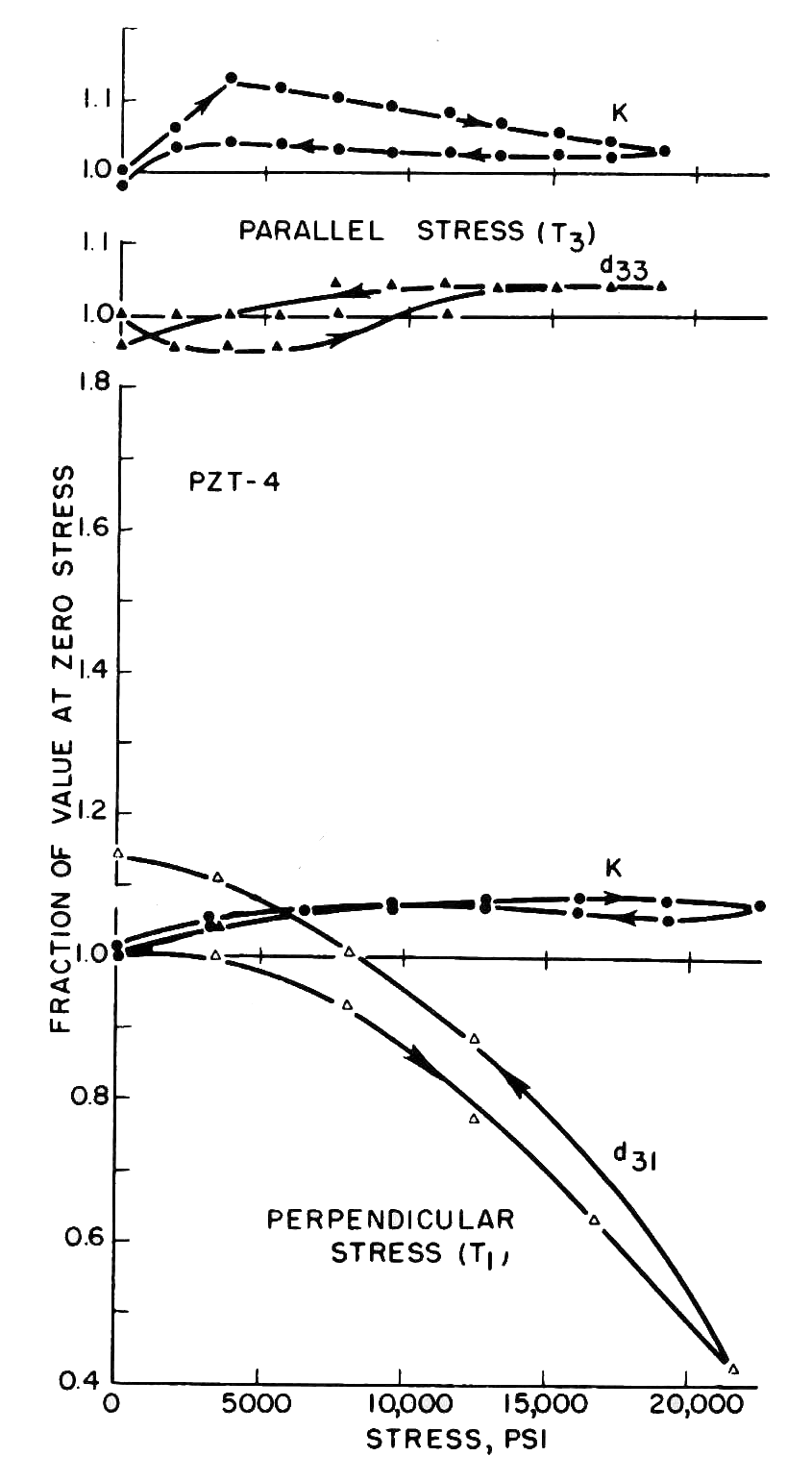

- For the 31 mode, figure A1(b) (Berlincourt (3), figure 16, p. 216) for PZT4 shows that there is a substantial decrease in \( d_{31} \)

with static compressive stress whereas \( d_{33} \) actually increases somewhat. Therefore, considerably lower compressive prestress can be tolerated in the 31 mode (Berlincourt (3), p. 249). This means that the dynamic ceramic strain, which is limited by the prestress, may be lower than desired and so the output amplitude may also be lower than desired.

Figure A1. Effect of compressive stress -

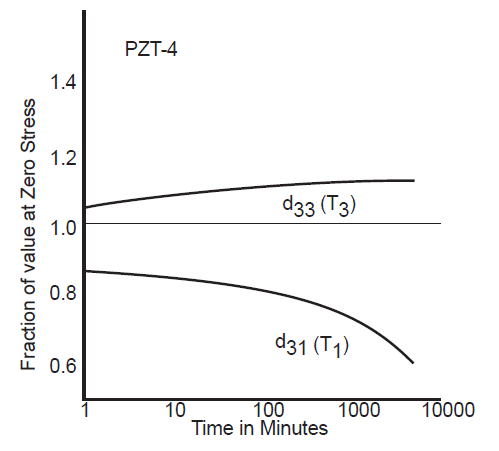

(a) 33 direction (top two graphs), (b) 31 direction (bottom graph) - Figure A2 (Morgan Technical Ceramics (4), p. 6) for PZT4 shows that there is a substantial decrease in \( d_{31} \) over time as the static preload stress is maintained. In contrast, \( d_{33} \) actually increases somewhat. For instance, at 1000 hours \( d_{31} \)

has decreased about 29% while \( d_{33} \) has increased about 12%.

Figure A2. Aging of \( d_{33} \) and \( d_{31} \) with 10,000 psi [69 MPa] stress

parallel (T3) and perpendicular (T1) to the poling axis

Recommendation

Except in special circumstances, the 33 mode should be used instead of the 31 mode.

Appendix B: Manufacturer's piezoelectric cross-reference

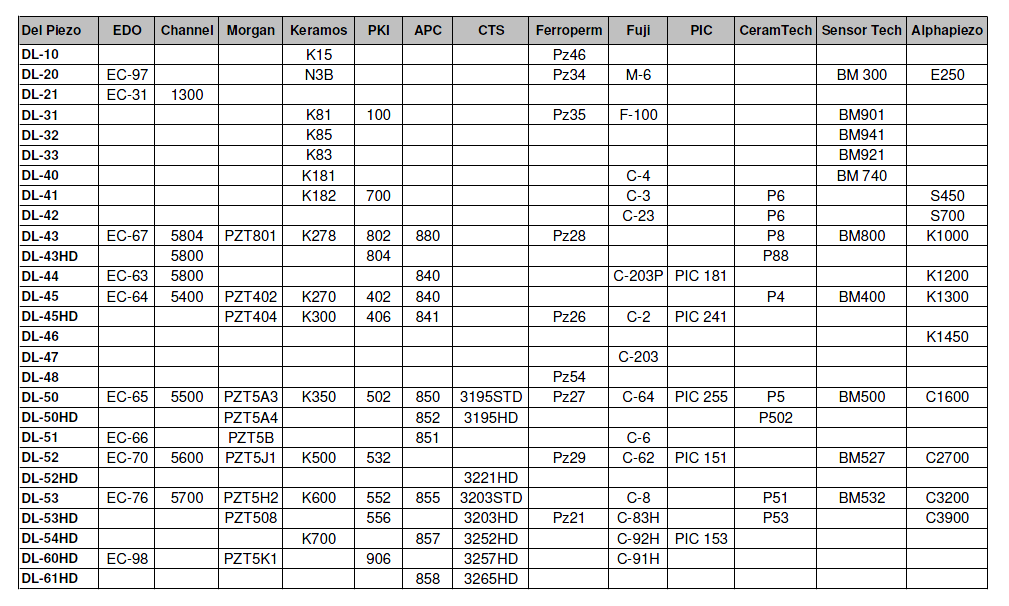

Table B1 gives cross references for nominally equivalent ceramics from selected manufacturers (courtesy of DeL Piezo Specialties).

|

||

|

Notes —

- PXE is a designation used by Philips.

- EBL is a designation used by Staveley Sensors.

- LTZ is a designation used by Transducer Products.

Appendix C: Method for applying prestress

"Repeated assembly and disassembly reduces the torque required." Waanders, p. 49

- Tightening stack bolt - averages nonuniform stress

- Using a press (Jones patent) - stress may be partially relieved when press force is released

Appendix D: Ceramic dimensional specifications

The following table gives ceramic dimensional specifications from various manufacturers.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Notes:

- Data is mainly from Prokic, pp. 6‑9, 6.1‑1.

- TIR = total indicator reading

- 1 light band = 0.000294 mm = 0.294 μm with a sodium light source

- K-Schliff = technical grinding that creates only a flat surface without consideration of the visual appearance (AUTANIA GRINDING TECHNOLOGIES)

- Ra = Roughness, average

- #2,000 = zzz

- zzz See Prokic comments p. 6-10; my notes p. 6-16

Appendix E: Ceramic electromechanical specifications

<< zzz d, capacitance, resonant frequency >>

Appendix F: Specifying mechanical fits

Neppiras (p. 301) asserts, "Dynamic frictional losses in the screw-threads account for most of the mechanical damping in the system, so that well-fitting threads are called for." This was echoed by Jones-Maropis transducer patent; DeAngelis.

Appendix G: Understanding piezoelectric constants

This appendix will show the relations between various piezoelectric parameters and constants.

Notes —

- The following discussion uses symbols that are commonly found in the piezoelectric literature. These differ from symbols that are traditionally used for elasticity.

- The equations below typically use a single symbol to desigate a characteristic of the ceramic. Actually, however, this symbol often represents a matrix of property constants. For example, the elastic compliance is designated by \( s \) which is actually the matrix —

|

||||||||||||

|

\begin{align} \label{eq:10099} \nonumber s = \left[ \begin{matrix} s_ {11} &s_ {12} &s_ {13} &0 &0 &0 \\ s_ {21} &s_ {22} &s_ {23} &0 &0 &0 \\ s_ {31} &s_ {32} &s_ {33} &0 &0 &0 \\ 0 &0 &0 &s_ {44} &0 &0 \\ 0 &0 &0 &0 &s_ {55} &0 \\ 0 &0 &0 &0 &0 &s_ {66} \\ \end{matrix} \right] \end{align}

These matrices are not needed to understand the following discussion.Basic piezoelectric relations

All solids deform when subjected to an applied force. The relation between strain \( S \) and stress \( T \) is —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10001a} S &= s \,T \end{align}

where \( s \) (lower case) is the material's compliance (the inverse of Young's modulus). This equation assumes a linear relation between \( S \) and \( T \), at least over the range of interest. This linearity will be assumed for all subsequent equations.

If a material is dielectric then the relation between the charge \( D \) and the applied electric field \( E \) is —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10002a} D &= \varepsilon \,E \end{align}

where \( \varepsilon \) is the permittivity of the material. The above parameters are summarized in table G2.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Note that equations \eqref{eq:10001a} and \eqref{eq:10002a} do not involve any piezoelectric effects (i.e., there is no interaction between the mechanical effects of equation \eqref{eq:10001a} and the electrical effects of equation \eqref{eq:10002a}). If a material is piezoelectric then additional terms must be added to account for the piezoelectric effect. One piezoelectric effect is that applying an electric field will cause a strain in the material (this is called the inverse or converse piezoelectric effect). Thus, equation \eqref{eq:10001a} must be modified by adding the term \( d^T E \) to account for this effect.

\begin{align} \label{eq:10003a} S &= s^E \,T + d^T \,E \end{align}

where \( d \) is the piezoelectric charge constant (see table G3) (The superscripts, which denote constraints, are explained below).

A second piezoelectric effect is that an external stress will cause a charge to build up in the material (this is called the direct piezoelectric effect as was first investigated by the Curies). Then equation \eqref{eq:10002a} must be modified by adding the term \( d^E T \) to account for this effect.

\begin{align} \label{eq:10004a} D &= \varepsilon^T \,E + d^E \,T \end{align}

where \( d \) is again the piezoelectric charge constant.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Note that if \( d \) = 0 (i.e., the material is not piezoelectric) then equations equations \eqref{eq:10003a} and \eqref{eq:10004a} just reduce to equations \eqref{eq:10001a} and \eqref{eq:10002a}, respectively. Hence, the piezoelectric characteristics of the material are defined by the charge constant terms \( d^T \) and \( d^E \).

Superscripts (constraints). A superscript on one of the constants indicates that the superscript is being held constant. For example, consider the strain parameter \( S \) with the superscript \( E \) (i.e., \( s^E \)) in equation G3. \( s^E \) indicates that the electric field strength \( E \) is held constant when the elastic compliance \( S \) is determined (e.g., when the material is stress-strain tensile tested). If \( E \) were not held constant then part of the strain \( S \) would result from the piezoelectric effect of \( d^T E \) and the measured value of \( S \) would not be correct. (In a similar manner, the temperature is kept constant during a stress-strain tensile test so that the strain is only affected by the stress, not by any thermal expansion.) Similarly, the dielectric constant \( \varepsilon \) in equation G4 can only be properly evaluated when the stress \( T \) is held constant (i.e., \( \varepsilon^T \)). Otherwise, part of the dielectric displacement \( D \) would be due to the stress \( T \) rather than the electric field \( E \) and the measured value of \( \varepsilon \) would not be correct. Common constraints are summarized in table G3a.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Table G3a notes:

- A state of constant strain cannot be practically achieved by physically restraining the piezoelectric ceramic. However, it can be achieved by exciting at a very high frequency where the inertial effects become so large that the ceramic effectively cannot vibrate (i.e., there are no strains). (See Cady (1), pp. 328, 572.) The same situation occurs when a single degreeoffreedom spring-mass system is excited at a frequency that is very high compared to its resonant frequency — the mass will not move from its rest position.

Equation notes:

- Equation \eqref{eq:10003a} says that the strain \( S \) can be changed by changing the applied stress \( T \) and/or by applying an electric field \( E \). If the material were not piezoelectric then the electric field \( E \) would have no effect and \eqref{eq:10003a} would reduce to \eqref{eq:10001a} — i.e.,

\begin{align} \label{eq:10005a} S &= s^E \,T \end{align}

the usual strain-stress relation. (The same result is obtained if the ceramic electrodes are short circuited so that no electric field is possible.) Thus, \( d^T E \) is the coupled piezoelectric factor.

- Equation \eqref{eq:10004a} says that the dielectric displacement \( D \) (i.e., the charge that is developed across the ceramic's electroded surfaces) can be changed by changing the applied stress \( T \) and/or by applying an electric field \( E \). If the material were not piezoelectric then the stress \( T \) would have no effect on the charge and \eqref{eq:10004a} would reduce to:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10006a} D &= \varepsilon^T \,E \end{align}

This is the usual relation between charge and electric field for a capacitor. (The same result is obtained if the ceramic electrodes are open circuited so that no current can flow.) Thus, \( d^E T \) is again the coupled piezoelectric factor. - Equations \eqref{eq:10003a} and \eqref{eq:10004a} are actually not complete since other pameters may affect the performance. For example, the strain \( S \) will change if the temperature of the material changes. Therefore, a term like \( \alpha H \) should be added, where \( \alpha \) is the coefficient of thermal expansion and \( H \) is the temperature rise. Thus, the temperature affects the strain similar to the effect of the electric field in a piezoelectric material. If the material were magnetostrictive then this effect should also be considered. Thus, the given equations implicitly assume that these effects are not present (for example, that the material is maintained at a constant temperature).

- Although equations \eqref{eq:10003a} and \eqref{eq:10004a} are often shown in this form, the variables can easily be rearranged to give alternate equations.

- The condition of constant electric field (constant \( E \)) is most easily achieved by short circuiting the ceramic's electroded faces so that no electric field can exist (i.e., \( E=0 \)).

- The condition of constant stress (constant \( T \)) is most easily achieved by not applying any external stress (i.e., the applied stress \( T \) = 0).

Significance of the charge constant d. The charge constant \( d^T \) is particularly important because it determines how much the material expands-contracts when an electric field is applied (termed the reverse piezoelectric effect for when the transducer is used as a transmitter). When the transducer is used as a receiver \( d^E \) determines how much charge is generated as the piezoelectric material is deformed (termed the direct piezoelectric effect). (The direct effect is relatively unimportant for industrial transducers except where a separate ceramic is used in the transducer as electrical feedback to monitor the transducer's amplitude.) In all cases a large charge constant is desirable.

Although \( d^T \) and \( d^E \) have different units, their numerical values in the S.I. system are identical (see Berlincourt (3), equation 24a, p. 188). Hence, equations G3 and G4 are generally written without the \( T \) and \( E \) superscripts on d.

\begin{align} \label{eq:10007a} S &= s^E \,T + d \,E \end{align}

\begin{align} \label{eq:10008a} D &= \varepsilon^T \,E + d \,T \end{align}

As mentioned above, these equations can be rearranged to give other constants. For example, solving equation \eqref{eq:10008a} for \( E \) and substituting into equation \eqref{eq:10007a} gives:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10009a} S &=s^{E} \,T + \frac{d}{\varepsilon^{T}}D - \frac{d^{2}}{\varepsilon^{T}} T \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &= s^{E} \,T + \frac{d}{\varepsilon^{T}}D - \frac{s^{E}}{s^{E}} \frac{d^{2}}{\varepsilon^{T}} T \nonumber \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &= s^{E}\left[1 - \frac{d^{2}}{s^{E} \varepsilon^{T}}\right] T + \frac{d}{\varepsilon^{T}} D \nonumber \end{align}

Equation \eqref{eq:10009a} can be simplified by consolidating the constant factors into two new constants — i.e.,

\begin{align} \label{eq:10010a} \kappa &=\frac{d}{\left(s^{E} \varepsilon^{T}\right)^{1/2} } \end{align}

\begin{align} \label{eq:10011a} g^{T} =\frac{d}{\varepsilon ^{T}} \end{align}

where —

|

|||||||||

|

(See Piezoelectric coupling coefficient for an alternate derivation of \( \kappa \) and a description of its significance.)

Then \eqref{eq:10009a} becomes:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10012a} S=s^{E} (1 - \kappa^{2}) \,T + g^{T} D \end{align}

If \( D \) is held constant (e.g., by disconnecting the electrodes (open circuit) so that no charge can flow — i.e., \( D \) = 0) then equation \eqref{eq:10012a} becomes:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10013a} S=\left[s^{E} (1 - \kappa^{2})\right] \,T \end{align}

Equation \eqref{eq:10013a} defines the relation between the strain and stress when the ceramic's electrodes are open circuit (i.e., \( D \) = constant). Hence, the factor \( s^E (1 - \kappa^2) \) is the compliance at open circuit. This open circuit compliance is denoted as \( s^D \):

\begin{align} \label{eq:10014a} s^{D} = s^E(1 - \kappa^{2}) \end{align}

Then substituting equation \eqref{eq:10014a} into equation \eqref{eq:10012a} gives:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10015a} S=s^{D} \,T + g^{T} D \end{align}

Compared to equation \eqref{eq:10003a}, the strain \( S \) in equation \eqref{eq:10015a} is now expressed in terms of parameters \( T \) and \( D \) with constants \( s^D \) and \( g^T \). The choice of using equation \eqref{eq:10003a} versus equation \eqref{eq:10015a} is completely arbitrary (although equation \eqref{eq:10003a} is more common).

Young's modulus

Equation \eqref{eq:10014a} shows that the piezoelectric ceramic can have two distinct compliances, \( s^E \) and \( s^D \). This results from the coupling of the mechanical and electrical characteristics of the ceramic.

Equation \eqref{eq:10014a} is expressed in terms of compliances. However, since Young's modulus \( Y \) is just the inverse of the compliance \( s \) (i.e., \( Y=s^{-1} \)), equation \eqref{eq:10014a} can be written as —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10016b} \frac{1}{Y^D} = \frac{1}{Y^E}(1 - \kappa^{2}) \end{align}

or

\begin{align} \label{eq:10016a} Y^D=\frac{Y^E}{1 - \kappa^{2}} \end{align}

where —

| \( Y^D \) | = Young's modulus at open circuit |

| \( Y^E \) | = Young's modulus at short circuit |

(Note: Young's modulus is usually represented by \( E \). However, since \( E \) is used here for the electric field strength, Young's modulus is represented by \( Y \) instead.)

Thus, the ceramic has two different Young's moduli, depending on the electrical boundary conditions (short circuit or open circuit). Since \( \kappa \) is always less than 1.0, the open circuit modulus \( Y^D \) is always greather than the short circuit modulus \( Y^E \). The phyiscal reason is as follows.

Consider an open circuit ceramic that is subjected to a compressive force \( F \). Part of the energy of compression goes toward deforming the ceramic and part goes toward establishing an electric field (i.e., a charge separation due to the ceramic's capacitance). Now if the ceramic is short circuited then the electric field disappears. The energy of the electric field also disappears but, because this is a conservative system, that energy must be converted into another form of energy — in this case, additional deformation of the ceramic. Thus, the ceramic compresses more at short circuit than at open circuit so the Young's modulus at short circuit (\( Y^E \)) must be lower than the Young's modulus at open circuit (\( Y^D \)).

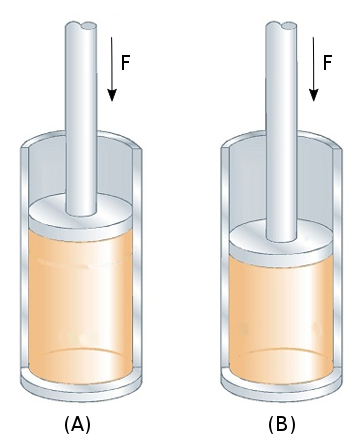

Compressed gas analogy

Consider figure G1 where a gas is compressed in a cylinder by a force \( F \). In the left image the cylinder is insulated so that no heat can escape. This is the adiabatic condition. During the compression process the temperature (thermal energy) of the gas has increased compared to its uncompressed state.

Now suppose that the excess thermal energy is allowed to drain off through the walls of the cylinder so that the temperature returns to its uncompressed state. With the loss of energy the gas can no longer support the piston at its previous position so the piston drops to a new equilibrium position (the right image). This is the isothermal (constant temperature) condition.

Thus the gas compresses more under isothermal conditions than under adiabatic conditions so the isothermal bulk modulus (\( B_T \)) must be lower than the adiabatic bulk modulus (\( B_S \)). This is similar to the piezoelectric modulus (\( Y \)) where the short circuit modulus (\( Y^E \)) is lower than the open circuit modulus (\( Y^D \)).

|

|

|

Short circuit and open circuit resonances

Since the ceramic has two Young's moduli, it must also have two associated resonances. The resonance that is associated with \( Y^E \) is called the short circuit resonance \( f_{sc} \). The resonance that is associated with \( Y^D \) is called the open circuit resonance \( f_{oc} \). (The short circuit resonance is also called series resonance; the open circuit resonance is also called parallel resonance. The reasons will be discussed elsewhere. zzz explain distinction) The relation between these resonances is shown below.

Since the resonant frequencies are proportional to the square root of Young's modulus (i.e., \( f\propto \sqrt{Y} \)), equation \eqref{eq:10016a} can be written in terms of short circuit resonance \( f_{sc} \) and open circuit resonance \( f_{oc} \) as:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10018a} {f_{oc}}^2={f_{sc}}^2 \left(\frac{1}{1 - \kappa^{2}} \right) \end{align}

or

\begin{align} \label{eq:10019a} {f_{oc}}={f_{sc}} \sqrt{\frac{1}{1 - \kappa^{2}} } \end{align}

where —

| \( f_{sc} \) | = short circuit resonance |

| \( f_{oc} \) | = open circuit resonance |

Note that \( \kappa \) has a value between 0 and 1 (see below) so the quantity under the radical of equation \eqref{eq:10019a} is always \( \geq 1 \). This means that the open circuit resonance \( f_{oc} \) will always be greater than the short circuit resonance \( f_{sc} \); the relative difference will depend on the coupling coefficient \( \kappa \).

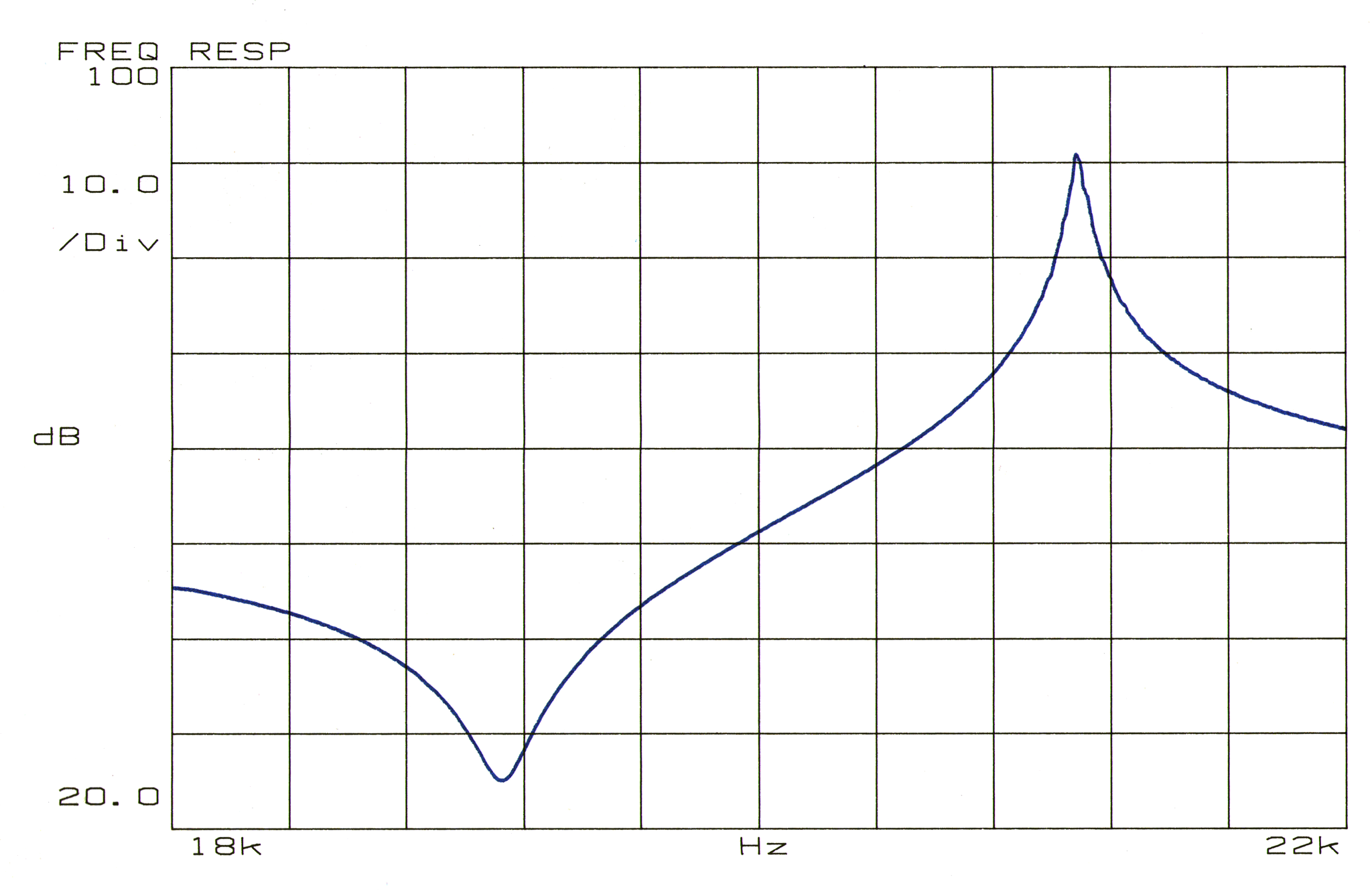

Figure G2 shows a frequency response impedance plot for the 20 kHz transducer (Branson 502) of figure 1. The impedance dip corresponds to the short circuit resonance \( f_{sc} \). The impedance peak corresponds to the open circuit resonance \( f_{oc} \). (This transducer does not have a front stud.)

|

|

|

Piezoelectric coupling coefficient κ

The energy that is stored in a piezoelectric material can take three forms — elastic (strain) energy, capacitive electrical energy, and coupled electromechanical energy. To show this, equations \eqref{eq:10003a} and \eqref{eq:10004a} can be expressed in terms of energies by multiplying \eqref{eq:10007a} through by \( T \)/2 and \eqref{eq:10008a} by \( E \)/2:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10020a} \small\frac{1}{2} \,S \,T &= \small\frac{1}{2} \,s^E \,T^2 + \small\frac{1}{2} \,d \,E \,T \end{align}

\begin{align} \label{eq:10021a} \small\frac{1}{2} \,D \,E &= \small\frac{1}{2} \,\varepsilon^T \,E^2 + \small\frac{1}{2} \,d \,E \,T \end{align}

Note that the energies in these equtions are actually energy densities (i.e., energy per unit volume).

In equation \eqref{eq:10020a}, \( \frac{1}{2} S \, T \) is the total stored mechanical energy. This is composed of the strain energy \( \widehat{W}_1 \) (\( = \frac{1}{2} s^E \, T^2\)) and the coupled piezoelectric energy \( \widehat{W}_{12} \) (\( = \frac{1}{2} d \,E \, T \)).

In equation \eqref{eq:10021a}, \( \frac{1}{2} D \, E \) is the total stored electrical energy. This is composed of the stored capacitive energy \( \widehat{W}_2 \) (\( = \frac{1}{2} \varepsilon^T \, E^2\)) and, again, the coupled piezoelectric energy \( \widehat{W}_{12} \) (\( = \frac{1}{2} d \,E \, T \)).

The coupling coefficient can be expressed in terms of the above energies as (Waanders (1), equation A8, p. 84 or Berlincourt (3), equation 30, p. 190) —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10022a} \kappa &= \frac{\widehat{W}_{12}}{(\widehat{W}_1 \,\widehat{W}_2)^{1/2}} \end{align}

where —

| \( \widehat{W}_1 \) | = Total stored mechanical energy |

| \( \widehat{W}_2 \) | = Total stored electrical energy |

| \( \widehat{W}_{12} \) | = Coupled piezoelectric energy |

Substituting the specific energy terms from equations \eqref{eq:10020a} and \eqref{eq:10021a} gives —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10023a} \kappa &= \frac{\frac{1}{2} \,d \,E \,T}{\left[(\frac{1}{2} \,s^E \,T^2) \,(\frac{1}{2} \,\varepsilon^T \,E^2)\right] ^{1/2}} \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &=\frac{d}{\left(s^{E} \, \varepsilon^{T}\right)^{1/2} } \nonumber \end{align}

Note that equation \eqref{eq:10023a}, which has been derived from energy considerations, is the same as equation \eqref{eq:10010a}.

For a single piezoelectric element, \( \kappa \) depends on the element's shape, mode of excitation (e.g., longitudinal, radial, thickness) and boundary conditions. Table G5 shows the most common conditions under which \( \kappa \) is evaluated for single piezoelectric elements.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The above defined coupling coefficients can be used when specifying or evaluating the performance of individual ceramics. They can also be used as reference values for comparison to completely assembled transducers.

The definition of equation \eqref{eq:10019a} can be applied to a ceramic of arbitrary condition (arbitrary shape, constraints, etc.) or to an entire transducer. For these cases, however, the terminology then becomes the effective piezoelectric coupling coefficient \( \kappa_{eff} \). (Alternately, \( \kappa_{33} \), \( \kappa_{31} \), \( \kappa_{t} \), \( \kappa_{p} \), and \( \kappa_{u} \) can be considered special cases of the more general \( \kappa_{eff} \).)

Any of the coupling coefficients can be calculated from their associated parallel resonance \( f_p \) and series resonance \( f_s \) frequencies (Waanders (1), equation A19a, p. 85).

\begin{align} \label{eq:10024a} \kappa _{eff} &= \left[\frac{{f_p}^2 - {f_s}^2}{{f_p}^2} \right]^{1/2 } \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &= \left[1 - \left({f_s}/{f_p}\right)^2 \right]^{1/2} \nonumber \end{align}

Since the parallel and series resonant frequencies are essentially independent of the transducer's mechanical and electrical losses (assuming that these are within reason), \( \kappa_{eff} \) can't be used as a criterion for the transducer's loss. For example, the following table shows that \( \kappa_{eff} \) is essentially the same for a Branson 20 kHz 502/932R transducer of either moderate quality or high quality (Prokic (1), pp. 22, 23).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Note — insofar as loss is concerned, a higher quality transducer will be characterized by —

- Lower resistance at series resonance

- Higher resistance at parallel resonance

- Higher \( Q \)

Significance of κ

Berlincourt (3), (p. 189) asserts, "The most important properties of piezoelectric materials are their piezoelectric coupling factors."

The significance of \( \kappa \) can be determined from equation \eqref{eq:10022a}. The numerator represents the converted energy while the denominator represents the input energy (Waanders (1), p. 12).

\begin{align} \label{eq:10025a} \kappa &= {\left[\frac{\text{Energy converted}}{\text{Energy input}} \right]}^{1/2}_{\text {Low frequency}} \end{align}

In order to achieve the maximum piezoelectric effect, it is desireable to convert much of the input energy into piezoelectric energy. Therefore, \( \kappa \) should be as large as possible by which equation \eqref{eq:10023a} shows that \( d \) should also be as large as possible (as previously discussed).

zzz -- relation to power output

Determining κeff

Appendix H: Effect of stack bolt on electromechanical coupling coefficient κ

When the ceramics are prestressed by a stack bolt, the electromechanical coupling coefficient \( \kappa \) is reduced because of the stiffness of the stack bolt. This appendix derives the relationship. (Note: in this discussion, "stack bolt" refers to any means of applying a prestress to the ceramic stack. This could include a center stack bolt, peripheral stack bolts, or a peripheral shell.)

See Transducer design — stack bolt for a general discussion.

Consider a ceramic that is contained between two rigid massless platens. When a D-C voltage \( V \) is applied, energy is transferred to the ceramic. Part of this energy charges the ceramic's capacitance. This energy is —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10028a} W_0=\small\frac{1}{2} \, C_0 \, V^2 \end{align}

where —

| \( W_0 \) | = Capacitive energy |

| \( C_0 \) | = Ceramic capacitance |

| \( V \) | = Voltage |

The rest of this energy causes the ceramic to expand; this is the desired effect by which the applied electrical energy is transformed into mechanical (strain) energy. This energy is —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10027a} W_k=\small\frac{1}{2} \, k \, X^2 \end{align}

where —

| \( W_k \) | = Strain energy |

| \( k \) | = Stiffness |

| \( X \) | = Displacement |

The electromechanical coupling coefficient \( \kappa \) is given by Waanders (1), p. 12 as:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10026a} \kappa^2 &= {\left[\frac{\textsf{Energy converted}}{\textsf{Energy input}} \right]}_{\textsf {Low frequency}} \end{align}

Note the requirement of "low frequency" so that the inertial energy due to acceleration is negligible compared to the strain energy.

The numerator of equation \eqref{eq:10026a} is just the strain energy \( W_k \) of equation \eqref{eq:10027a}. The denomintor is the total input energy (i.e., the combined energy of \( W_k \) and \( W_0 \)). Thus, equation \eqref{eq:10026a} can be written as:

\begin{align} \kappa^2 &=\cfrac{W_k}{W_k + W_0} \nonumber \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &= \cfrac{\frac{1}{2} \, k \, X^2}{\frac{1}{2} \, k \, X^2 + \frac{1}{2} \, C_0 \, V^2} \nonumber \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing \label{eq:10029a} &= \cfrac{1}{\left( \cfrac{C_0}{k} \right) {\left( \cfrac{V}{X} \right)}^2 +1} \end{align}

To see the effect of the stack bolt we can consider two cases.

- No stack bolt.

- A stack bolt is present.

Equation \eqref{eq:10029a} is perfectly general. Then it can be applied when there is no stack bolt (call this case 1) and when a stack bolt is present (call this case 2).

Case 1 — no stack bolt

Assigning subscript 1 in equation \eqref{eq:10029a} to indicate that no stack bolt is present:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10030a} {\kappa_1}^2 &= \frac{1}{{\left(\Large\frac{C_0}{k_1}\right) } \left(\Large\frac{V}{X_1} \right)^2 +1} \end{align}

Solving for \( \left(\frac{V}{X_1}\right)^2 \) (for later use):

\begin{align} \label{eq:10031a} \left(\frac{V}{X_1} \right)^2= \frac{\Large\frac{1}{{\kappa_1}^2} -1}{\left(\Large\frac{C_0}{k_1}\right) } \end{align}

Case 2 — with stack bolt

Assigning subscript 2 in equation \eqref{eq:10029a} to indicate that a stack bolt is present:

\begin{align} {\kappa_2}^2 &= \frac{1}{{\left(\Large\frac{C_0}{k_2}\right) } \left(\Large\frac{V}{X_2} \right)^2 +1} \nonumber \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing \label{eq:10032a} &= \frac{1}{{\left(\Large\frac{C_0}{k_2}\right) } \left(\Large\frac{V}{X_1} \right)^2 \left(\Large\frac{X_1}{X_2} \right)^2 +1} \end{align}

Here we are assuming that the displacement of the ceramic and bolt are identical (i.e., \( X_2 \)) as required by the massless platen to which they are attached.

For a given ceramic configuration the displacement \( X \) depends only on the associated stiffness. Thus, generally —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10033a} X \,\propto \, \frac{1}{k} \end{align}

Then the relative displacements without and with a stack bolt are —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10034a} \frac{X_1}{X_2} = \frac{k_2}{k_1} \end{align}

Substituting equations \eqref{eq:10031a} and \eqref{eq:10034a} into equation \eqref{eq:10032a} and simplifying gives —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10035a} {\kappa_2}^2 &= \frac{1}{ \left(\Large\frac{1}{{\kappa_1}^2} -1 \right) \left(\Large\frac{k_2}{k_1}\right) +1} \end{align}

The total stiffness \( k_2 \) just equals the ceramic stiffness \( k_1 \) plus the bolt stiffness \( k_b \) —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10036a} k_2 = k_1 + k_b \end{align}

Substituting equation \eqref{eq:10036a} into equation \eqref{eq:10035a} gives —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10037a} {\kappa_2}^2 &= \frac{1}{ \left(\Large\frac{1}{{\kappa_1}^2} -1 \right) \left(\Large\frac{k_b}{k_1} +1\right) +1} \end{align}

where (finally):

| \( \kappa_2 \) | = piezoelectric coupling coefficient with the stack bolt |

| \( \kappa_1 \) | = piezoelectric coupling coefficient without the stack bolt |

| \( k_b \) | = bolt stiffness |

| \( k_1 \) | = ceramic stiffness |

This is the same as the equation given by Berlincourt (3) (p. 269, endnote 9, referenced on p. 249), although with slightly different notation and some rearranging. If there is no bolt (so \( k_b = 0 \)) then \( \kappa_2 = \kappa_1 \), as expected. As the bolt stiffness \( k_b \)increases, \( \kappa_2 \) is progressively reduced below \( \kappa_1 \).

In terms of the actual ceramic and bolt parameters, equation \eqref{eq:10037a} can be written as —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10038a} {\kappa_2}^2 &= \frac{1}{ \left({\Large\frac{1}{{\kappa_1}^2}} -1 \right) \left({\Large\frac{Y_b \, A_b}{Y_c \, A_c}} +1\right) +1} \end{align}

where —

| \( Y_c \) | = Young's modulus of ceramic |

| \( A_c \) | = cross-sectional area of ceramic (i.e., the area of the ceramic's flat face) |

| \( Y_b \) | = Young's modulus of bolt |

| \( A_b \) | = cross-sectional area of bolt shank |

Appendix I: Resonance packet (pair)

A transducer can be considered to be a black box with electrical input and mechanical output. In-so-far as the primary resonance and its associated response are concerned, the black box can be approximately represented as a lumped equivalent electrical circuit. Various equivalent circuits have been proposed but the simplest is shown below.

This circuit has two branches —

- The mechanical branch — \( L_{M} \, C_{M} \, R_{M} \). This branch would characterize the transducer if the ceramics had no piezoelectric properties.

- The electrical branch — \( C_{0} \, R_{0} \). This branch accounts for the piezoelectric properties.

Starting first with the left branch, the current through this branch is given by —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10027z} I_0 &=E \, \frac{1}{\left[R_0 + \large\frac{-j}{\omega C_0} \right] } \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &=E \, \frac{1}{\left[R_0 + \large\frac{-j}{\omega C_0} \right] } \left\{\frac{\left[R_0 - \large\frac{-j}{\omega C_0} \right]}{\left[R_0 - \large\frac{-j}{\omega C_0} \right] }\right\} \nonumber \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &=E \, \frac{\left[R_0 - \large\frac{-j}{\omega C_0} \right]}{\left[R_{0}^{\;2} + \left(\large\frac{1}{\omega C_0}\right)^2 \right] } \nonumber \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &=E \left[\frac{R_0}{Z_0^2}\right] + j E \left[\frac{1}{Z_0^2}\left(\frac{1}{\omega C_0}\right) \right] \nonumber \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &= I_{R_0} + j I_{C_0} \nonumber \end{align}

Appendix J: Comparison — series resonance and parallel resonance

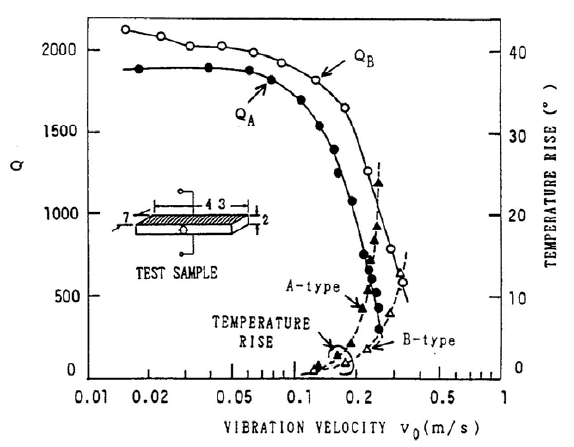

Hirose (1) considered the loss (Q) of a single piezoelectric ceramic that was driven longitudinally in the 31 mode. He discusses the causes of ceramic loss (section 3) and shows that (theoretically) antiresonant operation (parallel resonance) should have lower loss than resonant operation (series resonance). The experimental results in section 5 agree with this conclusion. In figure 2, the quality factor \( Q_B \) for antiresonance is higher than \( Q_A \) for resonance, while the temperature rise (due to loss) for antiresonance is lower than for resonance. Note that the results are for a single ceramic whose length is resonant. Presumably, the results are still valid for a non-resonant ceramic that is part of a complete transducer.

|

|

|

Prokic (1) conducted power loading tests on Branson 20 kHz transducers. The power was measured in air with an attached bell horn and then as the bell horn was progressively immersed in water. The transducer amplitude was maintained at 20 microns peak-to-peak.

Both in air and up to moderate loading, these tests showed that parallel resonance has lower loss than series resonance. (It should be noted that Branson's transducers are designed to operate at parallel resonance so the ceramic thickness and number of ceramics may not have been optimized for series resonance. For example, since series resonance requires lower drive voltage, fewer but thicker ceramics can be used without concern of electrical arcing.)

Power supply considerations

Compared to series resonance, parallel resonance has a very high impedance so that the current is low for a given power output.

Parallel resonance --> high voltage ==> ceramic thickness is limited by max allowed field strength.